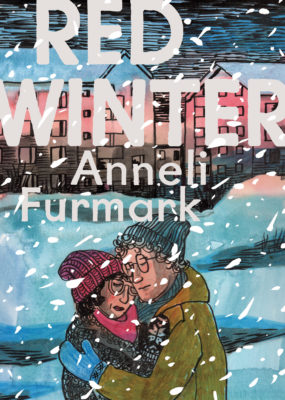

The heartfelt and melancholic story in Red Winter covers just a few days of a passionate love affair during a frigid winter in a small Swedish steel-mill town in the 1970s. But it is broader in its emotional scope: it delivers a lovely snapshot of the lives of ordinary people, including their stifled desires, isolation, loss of prospects, and political hopes.

It is the first comic book by Anneli Furmark to be translated into English. Furmark, who is also a painter, is one of the most celebrated cartoonists in her country. She published several books in the last two decades and won an Adamson Award and three Urhunden Prizes from the Swedish Comics Association, including one for Red Winter.

The two clandestine lovers in Red Winter are Siv, a married woman pushing forty with three children, and Ulrik, a much younger communist activist. Politics complicate everything: Siv is a member of the Social Democratic Party and her husband is a Social Democrat union member, while Ulrik is a staunch Maoist. Siv and Ulrik’s romance is central in a narrative that is dominated by Siv but approached polyphonically, with each chapter told from the point of view of a different character: Siv’s children and husband, Ulrik’s communists comrades, and Ulrik and Siv themselves.

Red Winter

Anneli Furmark

Translated by Hanna Strömberg

Drawn & Quarterly

$24.95

paper

168pp

9781770463066

Furmark is a gifted writer, and the translation feels natural and gracious. She has an excellent ear for dialogue that feels genuine without being trite. She depicts small moments with depth, and large moments with tenderness. When Siv’s daughter, Marina, is alone at home snooping or hanging out with a friend, we feel that odd, sombre nostalgia of childhood: the playful doing nothing that teaches us who we are, the anxiety of not knowing enough of the adult world and wanting to know more, while at the same time knowing perhaps too much (she finds out about the affair; she discovers “forbidden” magazines in the house). Peter, Siv’s son, immersed in his own teenage alienation from people and his environment, is presented with great compassion. Börje, the betrayed husband, personifies the ethos of a working-class man who “knows his place” in society, who is dependably boring. And Siv and Ulrik are just disoriented in their divided loyalties to family, to the Party, and to each other, and in the end they have little control over their destiny in a world where his idealism does not pay off and her pragmatism is insufficient.

The art delicately conveys those moods. Mainly in cold blues of the outdoors with warm red and orange highlights in cozy interiors, it wraps the narrative in loose and spontaneous watercolours. The relaxed lines make even harsh moments tolerable, while the sweetest scenes remain restrained – and slightly claustrophobic. The drawings are textured and layered, much like the situations, and express Furmark’s affection and generosity toward her characters.

Red Winter is the first book in a trilogy about the lives of ordinary people in northern Sweden. Here’s hoping that publishers will offer English readers an opportunity to appreciate more work from this talented author. mRb

0 Comments