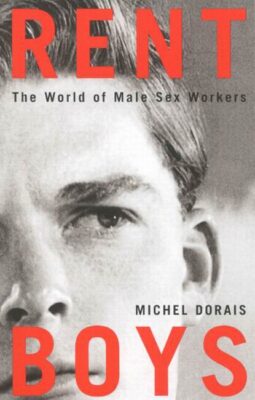

Rent Boys: The World Of Male Sex Trade Workers

Michel Dorais

McGill-Queen's University Press

$19.95

paper

136pp

0-7735-2903-9

Christophe, Jean-Loup, and Billy are prostitutes who service other men. They represent the divergent lives of forty male sex trade workers interviewed by a Université Laval research team for a study on the strategies young sex trade workers use to avoid HIV/AIDS. Funded through a Health Canada grant, the project also allowed Michel Dorais an opportunity to expand on an earlier work, Les enfants de la prostitution, written with Denis Ménard in 1987 and published by VLB Éditeur.

Rent Boys is by no means pure scientific research. More potential interviewees said no than said yes. Most positive responses came from street hustlers, since male strippers and escorts could earn more than the $20 an hour that the interviewers offered for their time. And, obviously, many workers crave anonymity, a factor that may or may not have skewed the conclusions.

Dorais, a social worker, divides the interviewed male sex trade workers into four categories. “Outcasts” – half the subjects – are generally the product of violent, dysfunctional homes. Most are drug users with few life choices and low self-esteem. “Part-timers,” on the other hand, are often married with children and have a “real” job that doesn’t cover expenses. Of the four groups, they are the most health-conscious and the least likely to take chances on HIV/AIDS infections. “Insiders” grew up around the sex trade, see it as a job, and don’t stick long to regular employment. (“The street is the only place I know where I feel at home,” says one.) “Liberationists” are young homosexuals, generally with less troubled childhoods, who use prostitution as a way of living out their fantasies. Researchers were not able to connect with male models, high-level body builders or young actors – examples of more affluent and perhaps more discreet workers. The book draws few specific conclusions, relying mostly on anecdotal evidence and personal accounts.

“Liberationists” and “Part-timers” believe they have made their own choices, while “Outcasts” and “Insiders” consider themselves victims. However, all groups tend to be badly educated, with few sustainable interpersonal or job skills. What genuine choices do they have? “The dangerous thing is to lose control. If the client is really determined, I might do it without a condom, but I’m the one in control,” one says, but many of them use drugs or alcohol – known control-inhibitors – while they are working.

The war on prostitution closed the brothels and opened up a market in street corner soliciting, a practice Dorais recommends legalising. Sex work, he says, offers no easy exit. Male prostitutes aren’t controlled by pimps, but the transition to a conventional job or adult education is difficult. The solution, he says, is to develop a more caring and tolerant society that reaches out to marginalised individuals such as the young people who practice sex work. “We have, as a society, the resources necessary to help prostitutes move on in life, as long as these are made genuinely available, accessible, and welcoming,” he insists.

Unfortunately, his study doesn’t leave us with any profound understanding of the physical, mental, and social health consequences faced by male sex trade workers, or with a sense of them as real people. We are left with glimpses of marginal lives lived out in a shadowy world. Perhaps that sad and disquieting vision was the one Dorais wanted to create. mRb

0 Comments