A wonderful self-awareness runs through “Strange Bewildering Time”, Mark Abley’s gorgeous and lyrical memoir of travelling overland from Istanbul to Kathmandu in 1978.

“What sounds do foreign travellers hear?” asks the now older and wiser writer, looking back on a dreamscape in which his twenty-two-year-old self has just arrived in northwestern Iran. “And what sights does the foreign traveller see and recall?”

The question is more complex than it first seems. And Abley’s attempts at finding answers – often unsparingly self-critical – are what elevate this book above the pack in the crowded field of travel literature.

Abley was studying at Oxford when he and travel partner Clare Gittings, “hungry for enlightenment” or adventure or both, set out to travel the Hippie Trail, a loose route catering to Western backpackers that, in its full extension, stretched from London all the way to Bangkok.

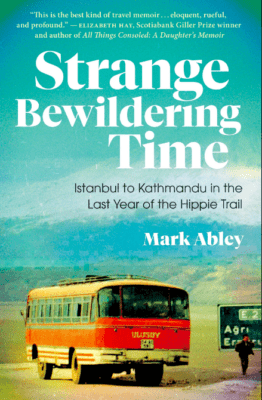

Strange Bewildering Time

Istanbul to Kathmandu in the Last Year of the Hippie Trail

Mark Abley

House of Anansi Press

$22.99

paper

296pp

9781487009663

A large part of the self-critique is found in Abley’s mixed feelings about the young stoners, hippies, and privileged idealists who took advantage of robust exchange rates to live out their fantasies of Orientalism. There are passages in which he cringes at the thoughtless young man that he was and the entitled nature of Western travellers, many of whom cared more about getting blitzed on cheap drugs than the complex and ancient cultures in which they found themselves:

Edward Said is referenced early on to describe the situation: “A certain freedom of intercourse was always the Westerner’s privilege; because his was the stronger culture, he could penetrate, he could wrestle with, he could give strength and meaning to the great Asiatic mystery.” Keenly aware of this lopsided dynamic, Abley writes: “Our vision quests overlapped with their everyday lives.”

It’s an important point, and one that is central to the memoir. His reflections on the subject are refreshing and pertinent, as he recreates a version of who he was at the time – waxing lyrical in Turkey, irritable and overwhelmed in India, or refusing to give up his train seat to less fortunate locals in Pakistan.

There is a poignancy in Abley’s belief that Iran and Afghanistan would inevitably embrace liberal democracy: “Lots of women in Tehran sported lipstick and chic Western clothes… Surely the future would sidle up in halter tops, not chadors. Surely religious extremism was a thing of the past.” And there are powerful ruminations on everything from the current rise of ethnic nationalism in India, to the intersection of development and environmental decline in Nepal:

Believers in the doctrine of progress can point to Nepal with pride, sidestepping all doubts as to whether the progress is sustainable. Is it sentimental – or colonialist even — if I mourn (…) the ruin of its wild spaces? I have no right to tell a Nepali farmer to stop cutting down trees. But neither can I repress my sorrow: the snow leopard, once gone, will never reappear. Nor will the red panda, the spiny babbler, the Himalayan yew.”

Veteran travellers will tell you that one of the virtues of seeing the world is in the illusions that are shattered, painful as this may be to bear. If Abley seems almost self-flagellating at times about his Western upbringing and privilege, his youthful decision to travel is justified by the worldview expressed in this book –- one of tolerance, humility, and compassion. Because if travel can afford us just a small modicum of empathy and wisdom to apply to our daily lives, that cannot be considered negligible.

There is poetry on every page of Strange Bewildering Time, and the sights and scents of Asia are rendered in vivid colours, whether Abley is writing about an endangered species of vulture or describing a Sikh temple with haiku-like economy.

By the end of this beautiful book, I thought maybe this was the point: that the distillation of experience into jewel-like sentences and clear images is the best we can do when it comes to untangling memory. That at the end of our journey, this is all we can hope for.

“I had to be content with a dawn breeze rustling through the marble latticework,” he writes. “I had to be content with rippled lamplight, reflected, floating high into the dome. And I was.”mRb

0 Comments