Bruce Sudds’ The Song of O’Sullivan’s Chain draws on Ireland’s Great Famine of 1845–52 to tell the story of successive generations of a family of immigrants, from their settlement in Kingston, Ontario in the mid-nineteenth century through the twentieth and twenty-first. It’s an ambitious work, in the sense that the familiarity of the material makes it a difficult book to pen for even the most talented of writers. By now, we’ve all absorbed so many stories of the Irish immigrant experience that it is a daunting task to bring a fresh twist to any new ones. And so, caveat scriptor.

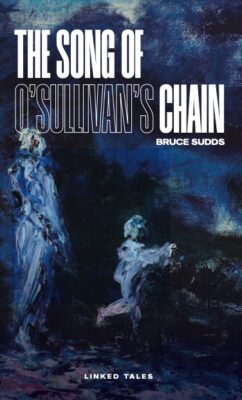

The Song of O’Sullivan’s Chain

Bruce Sudds

AOS Publishing

$20.99

paper

220pp

9781990496400

When a nation has been depicted in film, literature, and pop culture as often as Ireland has, we get into a thorny problem. Namely, that the tropes have been perpetuated into a kind of feedback loop that fuses romanticized legend onto more complex realities. As the descendant of a family that also emigrated from county Clare to Canada during the Great Famine, this critic can confirm that yes, the drinkers, carousers, and mulish hellraisers of yore existed. But the thing becomes problematic or caricatural when we stop realizing that other kinds of Irishness are possible, or when we become lazy in accepting certain dewy generalizations about the home country: the mist-drenched backdrops of the imagination, the verdant rural simplicity and ingrained suffering that led to boat-loads of gabby, fiddle-playing wanderers talking our ears off in pubs all over the world. Such overdone portrayals limit our ideas of what the Irish were and can be, as well as our potential to tell more interesting stories.

The novel takes an intriguingly political turn in its final chapters that merited further exploration. And there are some interesting ruminations on the nature of immigrant diasporas in Canada in general, such as when a character, returning from the U.S., mulls over our self-effacing tendencies: “What would strangers think of this place? How much did we want known? My Canadian family seems so inclined to resist being understood. Or even seen.” These astute sentences sum up a great deal of what’s wrong with Canadians’ relationship to history. We often don’t tell our tales the right way, out of some misguided sense of humility or restraint. And yet the stories are there. They just have to be told with a little more vitality and inspiration.mRb

0 Comments