One of the most memorable afternoons I’ve ever had was spent in the company of a ninety-three-year-old retired architect and budding cartoonist. Harry Mayerovitch was a man who had done well for himself; he was enjoying his golden years living in a spacious apartment in Côte-des-Neiges, with another apartment across the hall to store his collection of art and memorabilia. I was visiting him to talk about his book Way to Go, a collection of mordantly hilarious cartoons and visual puns around the theme of death and mortality.

“They’re a first-class operation,” Mayerovitch said of the Montreal-based publisher that had just brought out the book he had first pitched when he was a mere ninety. “Anyone who says young people today lack a work ethic should take a look at Chris and Drawn & Quarterly.”

Drawn and Quarterly

Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels

Tom Devlin with Chris Oliveros, Peggy Burns, Tracy Hurren, and Julia Pohl-Miranda

Drawn & Quarterly

$49.95

cloth

776pp

978-1-77046-199-4

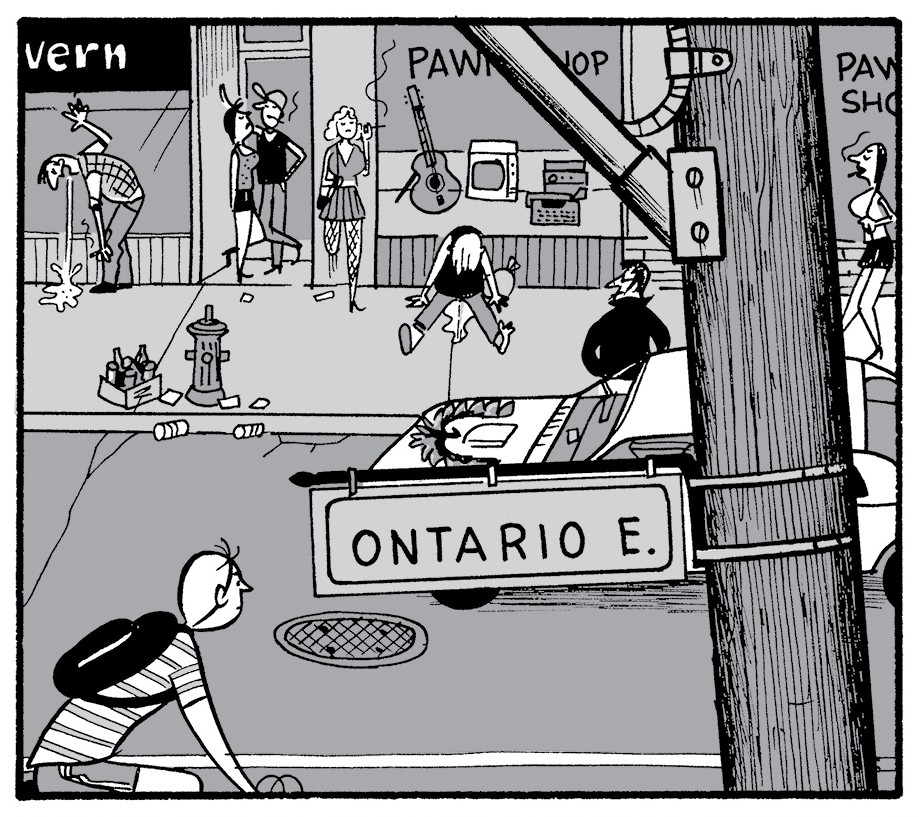

When I first moved to Montreal in the late 1990s and settled in Mile End, it pleased me greatly to know that I was walking the streets immortalized by Mordecai Richler and his creations. But soon enough I was getting just as much of a charge out of knowing that something special was unfolding in the neighbourhood in the here and now; its nerve centre, two small rooms above a travel agent on Avenue du Parc between Saint-Viateur and Bernard. It’s how I would guess it felt to be living in Detroit in the 1960s heyday of Motown, knowing that every time you went down West Grand Boulevard and passed that big old house with the Hitsville USA sign, something amazing was being cooked up behind those unassuming walls.

Comics hadn’t been a big part of my life since the fading of a childhood obsession with Mad magazine’s Don Martin. Beyond an abiding interest in Robert Crumb and a few outliers like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, I assumed that the form had passed me by. But then, via routes I couldn’t have foreseen, it began to sneak up on me again. One of my favourite albums of the early twenty-first century was Aimee Mann’s Lost In Space, a work whose mood of curdled romance was enhanced by – indeed inextricable from – its evocative cover art and lyric booklet. The CD package, it turned out, was designed, drawn, and lettered by Seth. Concurrently, one of my favourite books was by that selfsame Seth. Titled, rather brilliantly, It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken, the book was my introduction to both the manifold delights of the D&Q catalogue and to the idea that the comics medium can be a vessel for as broad a range of artistic statements as any other. Dots were connecting here. More and more of the coolest artefacts on the cultural landscape had one thing in common – the imprimatur of a company whose headquarters were literally right around the corner from my apartment.

The D&Q brand is the kind that earns your trust, and before you know it you can find yourself venturing into outré realms – Marc Bell’s intricate free-standing psychedelic tableaux, Anders Nilsen’s dream-logic minimalist epics – that you would previously have never considered. You can also find yourself going back into history and getting happily mired there. Tove Jansson’s Moomins have become so much a part of my life that I can scarcely recall how I got by without them, and it was the curatorial zeal of D&Q, and of Tom Devlin in particular, that brought those nearly forgotten Scandinavian trolls back into general circulation. The D&Q experience goes well beyond stars like Seth, Kate Beaton, Lynda Barry, Julie Doucet, and flagship titles like Guy Delisle’s Pyongyang and Chester Brown’s Louis Riel, the latter an especially groundbreaking work that continues to insinuate its way indelibly into Canada’s national cultural identity more than ten years after its publication. As the company’s new mind-blowing silver anniversary anthology demonstrates, it’s also about depth in numbers. Gathering this kind of plenitude between two covers is something precious few publishers could even conceive of doing; it’s overwhelming, but in a good way. If anyone still clings to the notion that comics are a poor relation in the family tree of literature, this is the book to crush such thoughts once and for all.

Over the years, I’ve had cause to write about D&Q and its books many times, and one of the first of those assignments involved a visit to that second-floor office on Parc. Stepping through the doorway from the street I saw that the indoor staircase was lined on both sides with boxes full of books; I made my way up by shuffling sideways. Upstairs, in among still more piles of boxes, was Chris Oliveros. He’s the most unassuming visionary you could imagine meeting – my strong sense was that here, stresses and vicissitudes of the publishing business notwithstanding, was a person doing exactly what he wanted with his life. My other abiding impression was of the seeming disjunct between the quantity and quality of what this office was producing and the size of what Mayerovitch called “the operation” – at this stage it was basically Oliveros and the newly hired spouse team of publicist Peggy Burns and designer/editor Tom Devlin. A common fallacy of pop culture history is the hindsight assumption that because something happened, it was inevitable. But that’s a view that gravely short-changes the contributions of people like Oliveros, Burns, and Devlin. They did more than just tap into the zeitgeist; in a very real sense, they helped create that zeitgeist.

Books, lest we forget, are objects. Central to the success of D&Q and kindred spirits like Fantagraphics and McSweeney’s is that, in an age when we’re forced to do more and more of our reading from screens, they’re providing something you just can’t get electronically. I lived out a nice demonstration of what this can mean roughly ten years ago, when, for reasons I can’t quite recall, I had to transport my copy of Chris Ware’s The Acme Novelty Library across the city on public transit. The outsized volume was literally too big to fit into any bag I could find, so I rode the metro that day with the book in full view. In the twenty minutes or so between Vendôme and Beaubien stations, I struck up two separate conversations with two complete strangers, our only common ground being our shared admiration for the immaculate design of the book in my arms. Years later, when Ware did an appearance at the Ukrainian Federation along with Charles Burns and Adrian Tomine, I saw those two people again, and we nodded in recognition. I like to think I had some small part in their being there. I don’t want to overplay this – it’s not like the three of us group-hugged and decided to move in together – but still.

Oh, and I almost forgot the store. Librairie Drawn & Quarterly, paid eloquent tribute by Heather O’Neill in the new anthology, has become the soul of Mile End in a remarkably short time – it’s our City Lights, our Shakespeare and Company. When I spoke to Junot Diaz on the eve of his visiting the city recently, I asked the Pulitzer-winning author of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao what was on his must-see list. He didn’t even pause. “Drawn & Quarterly,” he said.

Inevitably – and rightly – things do change over a quarter century, and Drawn & Quarterly, for all its admirable continuity, is no exception. The office has moved and grown, to an airy eighth-floor loft space in the industrial zone north of Mile End, and will shift this summer to an even bigger space nearby. The staff has grown, from one to three to eighteen. Unthinkably, Chris Oliveros will soon be stepping down to devote more time to his own cartooning, his place as publisher assumed by Peggy Burns. A part of me fears that if the company were to get much bigger, something – some essential ineffable underdog spirit – might be lost. But it’s only a very small part of me. These are smart people. I think this operation will stay first-class. mRb

0 Comments