Green pepper aficionados, weekend brunchers, and self-identified foodies beware: Jonah Campbell has no love for you. The Montreal-based author of

Food & Trembling, a collection of essays loosely united by gastronomy, does not tame his tastes for gentle readers. Indeed, his book perpetuates the tone of frank, black humour established in his blog, Still Crapulent After All These Years, which Campbell started in 2008. Despite Campbell describing it in a recent interview as being read only by “immediate friends … and people who get there from Google searching ‘deep-fried cheeseburger,’” the blog attracted the attention of the editors at Invisible Publishing. Food & Trembling includes many ideas originally presented online, though revised and expanded in order to shed what Campbell called “that ‘bloggy’ tone.”

Yet perhaps it’s because of this blog foundation that the book is so intriguing. Campbell is a mess of contradictions, singing the praises of caperberries in one essay and Doritos Late Night All Nighter Cheeseburger Flavored Tortilla Chips in the next; idealizing the authenticity of a chickpea shami offered by a literal hole-in-the-wall Montreal food counter here, yet perfectly happy to construct a soy milk- based béchamel there. When the book starts, Campbell is a margarine-savouring vegan, and by the book’s end, he’s an “energetic omnivore” dabbling in offal. Of course, the author is fully aware that his taste for the pure clashes with his penchant for the processed – he even spends an essay reflecting upon “Food As Destroyer” (i.e., why he persists in eating junk food when he’s sick). Food & Trembling is like sitting with a friend over a couple of pints and listening to him expound deliriously but endearingly. You can’t deny your friend his idiosyncratic cravings, can you?

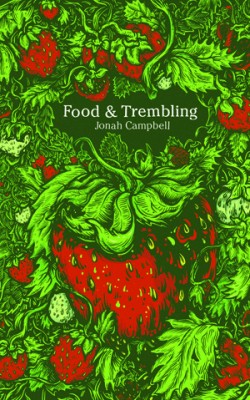

Food & Trembling

Jonah Campbell

Invisible Publishing

$17.00

Paper

232pp

78-1-926743-15-8

Campbell is the first to admit that he lacks any “professional” authority as a gourmet. In the essay “God Help Me,” he recounts his early experiences in the kitchen – first as a teenager relegated to making the family dinner each night, then as a resto “dish pig” (described briefly as “First Time I Got My Hand Covered With Maggots, First Time I Enjoyed Mushrooms, First Time I Felt Physically Angry At Mussels, First Time I Obscured My Tears In The Steam of a Dishwasher”), on to his associations with Food Not Bombs, and the beginning of his vegetarianism. Now Campbell is a master’s student in the Social Studies of Medicine at McGill, and a home chef with a real DIY spirit. He’s brewed chocolate- espresso stout in his own apartment, used torn-up beer boxes as a makeshift cutting board, and dumpster dived for donuts. Scroll through his blog and you’ll find a photo of a pig’s head boiling away on Campbell’s stove, a pair of sunglasses perched on its snout. An expert he is not, but he’s also not afraid to state his opinions and share his natural curiosities. He displays an admirable willingness to eat “off the beaten path.” As he says in “Not Much Pluck”: “It occurs to me that there has been a fundamental shift in my relationship to food over the past few years. Namely that disgust now plays a profoundly diminished role in determining what I eat.”

He insists (though his mother may believe otherwise) that it’s not bravado that leads him to sampling sautéed calf brains, but a desire to find “truth in the tastes of others.”

He insists (though his mother may believe otherwise) that it’s not bravado that leads him to sampling sautéed calf brains, but a desire to find “truth in the tastes of others.”

Campbell arrived in Montreal in 2005, intending to hitchhike from Ontario to his homeland of PEI, but decided that la belle province was just as good a place as any to settle. In Food & Trembling he relays several moments in which place and taste become perfectly fused in his memory – that delectable chickpea shami, for instance, stumbled upon in the most unlikely of spots here in Montreal. When asked how he regards the food landscape of the city, Campbell said he prefers a “sort of negative culinary map of Montreal.”

“On the one hand, it has this rep as a great food city, but a lot of the restaurants and the culture upon which that reputation rests are not really accessible to a lot of the populace,” he explained. “The food that I came to know and love when I first moved here is all of the street-level stuff, the cheap South Indian, Sri Lankan, and West Indian food of Côte-des-Neiges, the tali and Pakistani food of Park X, and all the little Middle Eastern and Chinese places that pepper the downtown core.” This mélange, he insisted, “provides the real topography of a city’s foodscape.”

And Campbell traverses this foodscape in the company of friends – the ex-pat’s new family with whom he breaks bread. Sampling native potato chips on a European tour, MacGyvering a repair to his apartment’s temperamental fridge (described in the very funny “I’ll Never See Such Arms Again, In Wrestling or in Love”), devising ways to cook with the aforementioned (stolen) case of caperberries: such are the adventures binding friends. The Orphan Christmases for punk immigrants that Campbell describes in Food & Trembling have since been replaced, he told me, by other rituals that build community, like last summer’s First Annual Octo-Q and Seafood Fest, “where we steamed a bunch of mussels and had smelts, and I tried to cook a whole octopus on the barbecue.”

All this is not to say that the book lacks gravity. There are finer details in Campbell’s self-portrait. The man loves words, to put it mildly. Many an essay begins with – or focuses entirely upon – an etymological profile of such rarer food-bent words as gulchin and petecure. In the book, he points to his father, with his “correct-if-uncommon kinds of wordplay,” for instilling an “interest in the directionality of word mechanics.” In our interview, he elaborated:

Analysis and critique are the source of some of the keenest and most ineffable pleasures of my life, and make up a big part of who I am. Most of the time the words we use are “black boxed,” as in, we use them and they do things for us, but we don’t give much thought to how they do what they do, and how they got there. I find opening those black boxes, or attempting to, through etymologies, a really satisfying and exciting process.

In Food & Trembling, Campbell extends the actions of analysis and critique to a dissection of food itself, and beyond that, his cerebral interactions with it – taste. Meals are itemized in language that surpasses the mere restaurant reviewer’s, even while maintaining a slight note of perversion (read with what reverence he describes his favourite “aromatic breakfast” of margarine, buckwheat honey, and harissa on toast, right down to the peculiarly successful interaction of spices in the Tunisian variety of harissa). Furthermore, it is not enough for the author to say he dislikes green peppers: he uses his dislike to ask whether it “reaffirms the unity of the self and the continuity of identity,” at the same time as deliberating the very truthfulness of the essential-self concept.

Although Campbell has been blogging for a while, food writing as a genre is a more recent discovery. He calls M.F.K. Fisher a favourite (in the book, top person “For Whom I Should Probably Invent A Time Machine For The Purposes of Seducing/Being Seduced By”) for managing to write about food with a sensuality “that never becomes trite.” Sharing the shelves with his well-thumbed Oxford English Dictionary are Grieve’s A Modern Herbal and Harold McGee’s On Food and Cooking. The literary figures that pop up referentially in Campbell’s book are many; in conversation, he stressed the particular influences of Maugham, Capote, and David Foster Wallace (“for not being afraid of indulging” – like Campbell – “in prolific footnotes in what are non-academic texts”). As for his own writing, Campbell recently completed a series for the National Post, and while another food book is not yet on the menu, he has been toying with the idea of assembling a second, much more extensive index to Food & Trembling, loving the “idea of an index that is simultaneously a tool and a puzzle.” And who would read this conceptual supplement? “Nerds, I guess,” he mused. “It’s something that I want to do, but then I can’t imagine anyone actually wanting it.” mRb

0 Comments