Stories of midlife crises invite deep reflection on the past, wishful thinking of the present, and trepidations about the future. In his second novel, Halbman Steals Home, B. Glen Rotchin attempts to convey the complexities of a middle-aged man at a crossroads, but the book feels a little too much like the other stories of midlife crisis out there.

Mort Halbman is the tragicomic protagonist; happiness has eluded him his entire life. His ex-wife got away from him once she started a collection of self-help books, and now seems to be flourishing with a new pompous partner. His son, whose homosexuality has always bothered Mort, announces that he is getting married and wants to find a progressive rabbi for the ceremony. His midlife crisis is exacerbated by a mysterious fire that burns down his old family home in Hampstead. To cope with all the rapid changes in his life, Mort keeps on revisiting the site of his old home, though he is not sure what he is looking for exactly.

As events unfold in Mort’s life, they also trigger a series of flashbacks, through which the reader learns of Mort’s past. Despite his career success (and his economic comfort), Mort’s life has been a series of disappointments and regrets. We learn about his passionless marriage to the daughter of a powerful garment industry mogul, his short stint in Los Angeles where he fails to “make it,” and his children’s rejection of the hetero-normative, bourgeois lifestyle Mort worked so hard to provide. Even Mort’s fanatic love of baseball is marred by the Montreal Expos’ 1981 loss.

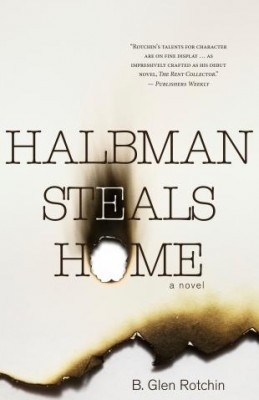

Halbman Steals Home

B. Glen Rotchin

Dundurn

$19.99

184pp

paper

978-1459701274

Rotchin addresses the ethnic segregation and tension between various Montreal communities, mostly through exchanges between Mort and a police officer of Italian descent. There’s a brief glimpse of Asian groceries and restaurants, passed by on one of Mort’s drives. Disappointingly, this exploration does not go beyond stereotypes and sensationalized media stories, such as crimes committed by the Italian mafia and tax fraud committed by Jewish merchants.

What stops the novel from being a truly immersive experience is its overactive plot; life seems to be showering Mort with one hardship after another. But the novel’s biggest problem is the lack of depth in all of the characters, who are caricatures. Perhaps the exaggerated nature of the characters has to do with the fact that the novel stays with Mort’s warped and bitter perspective. Seeing the events solely through his perspective, the reader never experiences the relief of a different family member’s version. This omission feels like a missed opportunity.

Halbman Steals Home does not provide deep insights about human nature or family relations, but it is entertaining and a quick read. The nostalgic overview of Montreal’s sad baseball history adds a bit of originality to a familiar tale. mRb

0 Comments