It’s October 16, 1970, the morning the War Measures Act is brought into force in Quebec. Fifteen-year-old Gaétan Simard, who has just started working in a textile factory, arrives at the apartment of his older friend Luc Maheu, also a factory worker. They’re about to go for a beer at the tavern after Gaétan’s overnight shift the first week on the job, when unexpected visitors arrive. Luc has been targeted by police for arrest for his role as union organizer and is taken away without warrant in the early morning light with no information as to where or for how long he will be detained. So begins Magali Favre’s sixth novel, 21 Days in October, and Gaétan’s tumultuous political awakening and coming of age.

Gaétan is from a struggling working-class family that includes his parents and two younger siblings. He experiences a new-found feeling of independence that comes from having taken the job at the factory, which strikes him as more relevant than going to school, where his grades were poor. Since his father is injured and cannot work, the position enables Gaétan to contribute to the family grocery bills. Because of this challenge and the different opinions his mother and father hold on the mounting October Crisis, the atmosphere in the Simard household is replete with tension. Mr. Simard is also arrested and the crisis serves as a catalyst for his political and economic frustrations. Mrs. Simard, on the other hand, is on the side of civic safety and supports Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau.

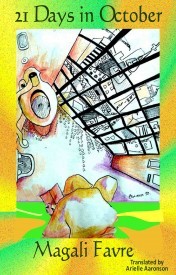

21 Days in October

Magali Favre

Translated by Arielle Aronson

Baraka Books

$14.95

paper

168 pp

978-1-926824-92-5

Gaétan is enmeshed in the overarching crisis and his struggles serve as a canvas for his growing political awareness. Event still, he often remains quite neutral as he tries to shrug off the political vexations of his parents. He is just and empathetic, simultaneously innocent and wise. He is unafraid to question those who have influence on him. This includes new friend and budding love interest, Louise. She is a radical political activist and culturally engaged CEGEP student who takes the time to listen to Gaétan. As time passes, she becomes an advocate for him and his family and exposes him to music, poetry, and a different way of living. She inspires him to reconsider his educational aspirations. Near the end of the novel when Louise suggests Gaétan would make a fine politician one day, the boy’s future becomes open to possibilities in a manner he had not considered.

The original French book was marketed to young adults as an educational tool for discussion, which explains the omniscient and didactic narrator that carries us through the story. While the narrator’s voice is consistent and never heavy-handed, there is the odd occasion when words feel askew in translation, as, for example, “Two large cardboard boxes serve as goals,” rather than as hockey nets. Regardless of this, 21 Days in October is a compassionate telling of Gaétan’s story and of a people’s story. The novel offers an important perspective for adults of any age, especially those who may not have lived in Quebec through the Quiet Revolution and during the October Crisis.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks