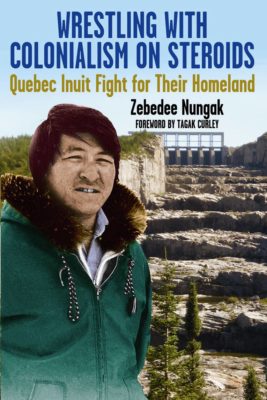

On the cover of Wrestling with Colonialism on Steroids, a portrait of author Zebedee Nungak appears superimposed on a photo of what Hydro-Québec calls “the giant’s staircase.” This spillway for the Robert-Bourassa Dam on the La Grande River boasts ten steps blasted from bedrock that each exceeds the span of two football fields. It is a tourist attraction of the James Bay region – symbolic of the monumental scale and technological prowess of a power-generating system that the Quebec government trumpeted as “the Project of the Century” when announcing plans to build it in 1971.

For the Inuit of Nunavik, however, the giant’s staircase conjures up the provincial Goliath that once threatened their homeland in northern Quebec with proposed hydroelectric installations on the Great Whale and Caniapiscau Rivers.

Zebedee Nungak was a twentysomething federal employee in Kuujjuaraapik (a village at the mouth of the Great Whale River) when he entered the fray to stop the James Bay hydroelectric project and then, when that proved impossible, to negotiate an agreement between the province and the Cree and Inuit inhabitants who would be impacted by the damming and diversion of rivers and the flooding of lands. He was one of eleven Inuit signatories to the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) in 1975.

Wrestling with Colonialism on Steroids

Quebec Inuit Fight for Their Homeland

Zebedee Nungak

Véhicule Press

$15.95

paper

129pp

9781550654684

For decades, the provincial government ignored northern Quebec. In a Supreme Court challenge during the Great Depression, it “argued emphatically that its Inuit citizens were ‘Indians,’ and therefore Canada’s responsibility.” It won the case, so the federal government introduced social welfare, built housing, and offered other services in Arctic Quebec.

In the 1960s, provincial authorities finally turned their attention to Nunavik, which they dubbed “Nouveau-Québec.” They francized Inuktitut and English place names and duplicated federal services. But they were more interested in the region’s natural resources than its then four thousand scattered Inuit residents. In 1970, Robert Bourassa made the James Bay project a major plank in his successful campaign to be elected premier. According to Nungak, “Not a passing thought was given to the rights of Aboriginal people.”

With no political experience, Inuit leaders – mostly young men like Nungak – formed an association and a sometimes uneasy alliance with Cree colleagues. They subsequently launched a court case to halt construction on the James Bay project. Nungak vividly captures the tensions between the parties concerned, the short-lived triumph of an injunction, and the frustrations of hammering out an agreement in the face of severe time constraints and government intransigence. He expresses profound sadness at the permanent rifts that were created amongst the Inuit by the government’s insistence on reducing Inuit-held territory to “small patches” in exchange for financial compensation and measures to allow the Inuit more control over their lives and environment. He concludes with a short political history of Nunavik since the JBNQA.

It is to be hoped that this fast-paced book will be translated into French so that more Quebecers will gain an understanding of what has transpired north of the 55th parallel from the perspective of an Inuk who has, as Tagak Curley puts it in the foreword, “a memory sharper than a harpoon.” And a pen sharper than a harpoon, too. mRb

0 Comments