Billy ...

By

On a warm, spring Easter Day afternoon, I visited the offices of Black Rose Books to speak with the members of the collective – Dimitrios Roussopoulos, Nathan McDonnell, Clara-Swan Kennedy, and Dan G. Reid – about the past, present, and future of this Montreal literary institution.

By Su J Sokol

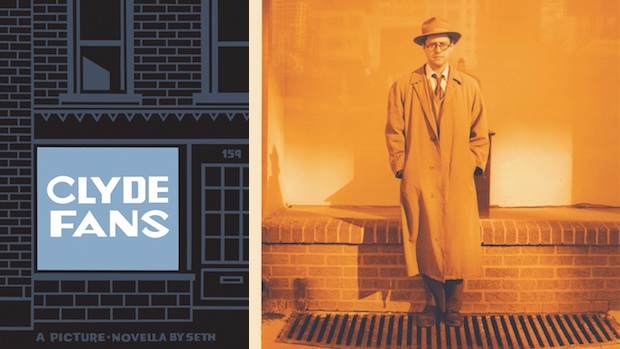

eth is a genre unto himself. The cartoonist, born Gregory Gallant, has been exploring and refining his singular ...

By Ian McGillis

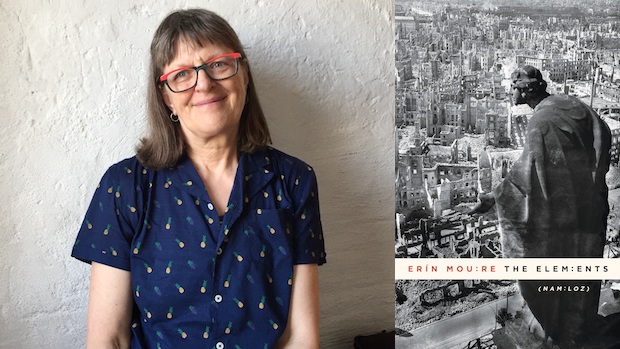

Erín Moure’s The Elements: (Namloz) begins, shoulders back, index finger up, with the words “In fact.” This gesture is a complex one because of the way Moure shifts between battle scenes, theory, and philosophy.

By T. Liem

What is creativity, and how does it work? Is creativity something that one has or one does? Adrian McKerracher’s What it Means to Write: Creativity and Metaphor is a layered meditation on how metaphors for creativity respond to these kinds of questions, even as they strive to express them.

By Emily Raine

Part of me wants to say that nîtisânak is the literary equivalent of a middle finger, sporting chipped black nail polish and waving in front of Nixon’s knowing smirk. At times it is, directing justifiable anger and irreverence towards racist, transphobic, and homophobic institutions, perceptions, and people.

By Alicia Elliott

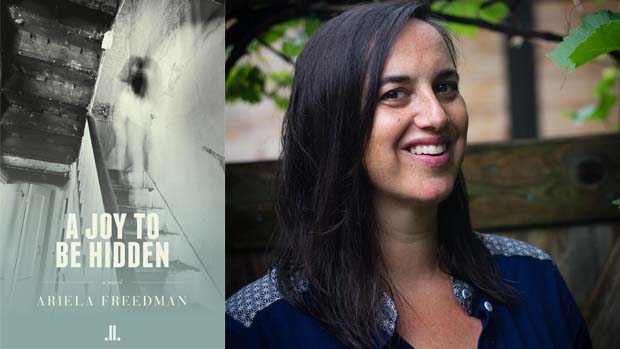

In classical mythology, Persephone is forcefully separated from her mother and taken to the underworld. She is eventually able to return, but the reunion is incomplete: Persephone must forever spend a portion of time hidden away, moving through a cycle of appearance and disappearance tied to the seasons. Through both indirect and direct reference, this myth infuses Ariela Freedman’s novel A Joy to Be Hidden, where secrets, loss, and separated family members interweave through multiple plot lines.

By Danielle Barkley

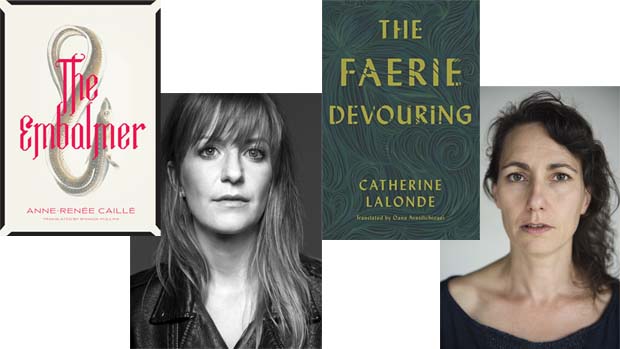

atherine Lalonde’s The Faerie Devouring likewise centres on an intimate familial relationship: the sprite, a young girl, is raised by her staunch grandmother among a gaggle of other children in rural Quebec. In contrast with the precise, crystalline images and mood of The Embalmer, Lalonde’s language is organic, pulsing, and repetitive in the way of fairy tales. The Faerie Devouring is a loose, impressionistic text that captures the fraught, shifting relationship between the sprite and her Gramma. Lalonde’s characters are physical before anything else, moving constantly but barely speaking.

By H Felix Chau Bradley

Expect neither Skil saws nor crowbars in Montreal writer and translator David Homel’s eighth novel: the “teardown” he explores with perspicacity is the mindset of a narrator who, like the older homes in his childhood neighbourhood, remains structurally sound but feels unjustly rendered worthless in a volatile, financialized new world order.

By Pablo Strauss

The storytelling tradition would never have become a tradition if people hadn’t been willing to work on variations of what came before, and in Sasquatch and the Green Sash, Henderson takes Sir Gawain and the Green Knight further afield than most would dare. Describing his project in the acknowledgements as “a hybrid thing, at once an adaptation, translation, and Canadianization,” he makes good on all three claims.

By Ian McGillis

At the centre of Didier Leclair’s beautifully written and realized novel, This Country of Mine, is Dr. Apollinaire Mavoungou, a recent immigrant from an African country to Toronto. His professional qualifications still unrecognized, despite passing the required local exams, Apollinaire works at a call centre and moonlights illegally as a doctor to retain some semblance of his former life.

By Veena Gokhale

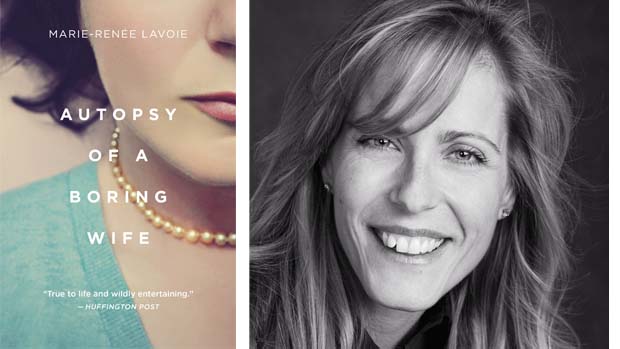

Diane Delaunais, the main character in Marie-Renée Lavoie’s novel Autopsy of a Boring Wife, is (despite the title) not at all boring. After Jacques, her husband of twenty-five years, unexpectedly leaves her and their empty nest near Quebec City for a younger woman, Diane’s equilibrium (if she ever had any) spirals out of orbit. Trying to regain her footing, she lurches from scene to scene in escapades often featuring her sympathetic friend Claudine.

By Cora Siré