As this year draws to a close, we thought we’d take a moment to reflect back on our reviews this past year and see what resonated most with you all. Reminiscent of our Fall 2023 Issue features’ focus on AI, the algorithm is both terrifying and fun to contend with. By examining our website’s traffic and analytics, we were able see which reviews stood out to our mRb audience – scroll down to discover them!

*

1. Fayne by Ann-Marie MacDonald (November 2022)

1. Fayne by Ann-Marie MacDonald (November 2022)

“Weighing in at 736 pages, Fayne, Ann-Marie MacDonald’s magnificent fourth novel, is a hefty read, yet never does it feel too long. Here, the best-selling author skillfully marries the mystical with the scientific, her nature-honouring opus illuminated with flashes of humour. She explores timeless themes like loyalty and betrayal within love and friendship, while addressing issues of gender and sex with great depth and sensitivity.” – Kimberly Bourgeois

2. Kukum by Michel Jean (July 2023)

2. Kukum by Michel Jean (July 2023)

“Kukum is an admirable book. Jean makes us feel the loss experienced by Quebec’s Innu community through a highly personal story. With Almanda as a narrator, the reader discovers and falls in love with Innu culture, just as she does. The growing immersion into their world makes the eventual tragedy of its loss that much more heart-wrenching.” – Roxane Hudon

3. Wapke by Michel Jean (March 2023)

3. Wapke by Michel Jean (March 2023)

“The collection, whose title is an Atikamekw word meaning ‘tomorrow,’ ‘is an opportunity to give Indigenous writers in Quebec a chance to say a word about the future, which we don’t get to do very often,’ Jean says. ‘Diversity is an option and a question in Indigenous communities,’ he continues. ‘People on the outside don’t realize that, but it’s a big deal. There are many different cultures, backgrounds, and histories within Indigenous nations in Quebec.'” – H Felix Chau Bradley

4. The Family Code by Wayne Ng (November 2023)

4. The Family Code by Wayne Ng (November 2023)

“In The Family Code, Hannah Belenko demonstrates that the darkest parts of herself must be reckoned with in order to come out the other side. From her story, Ng teaches us that family certainly provides us with the fuel for our own growth, although this sometimes means being far from their reach, and unlearning everything we believed about ourselves and the world around us so we can start anew.” – Phoebe Yī Lìng

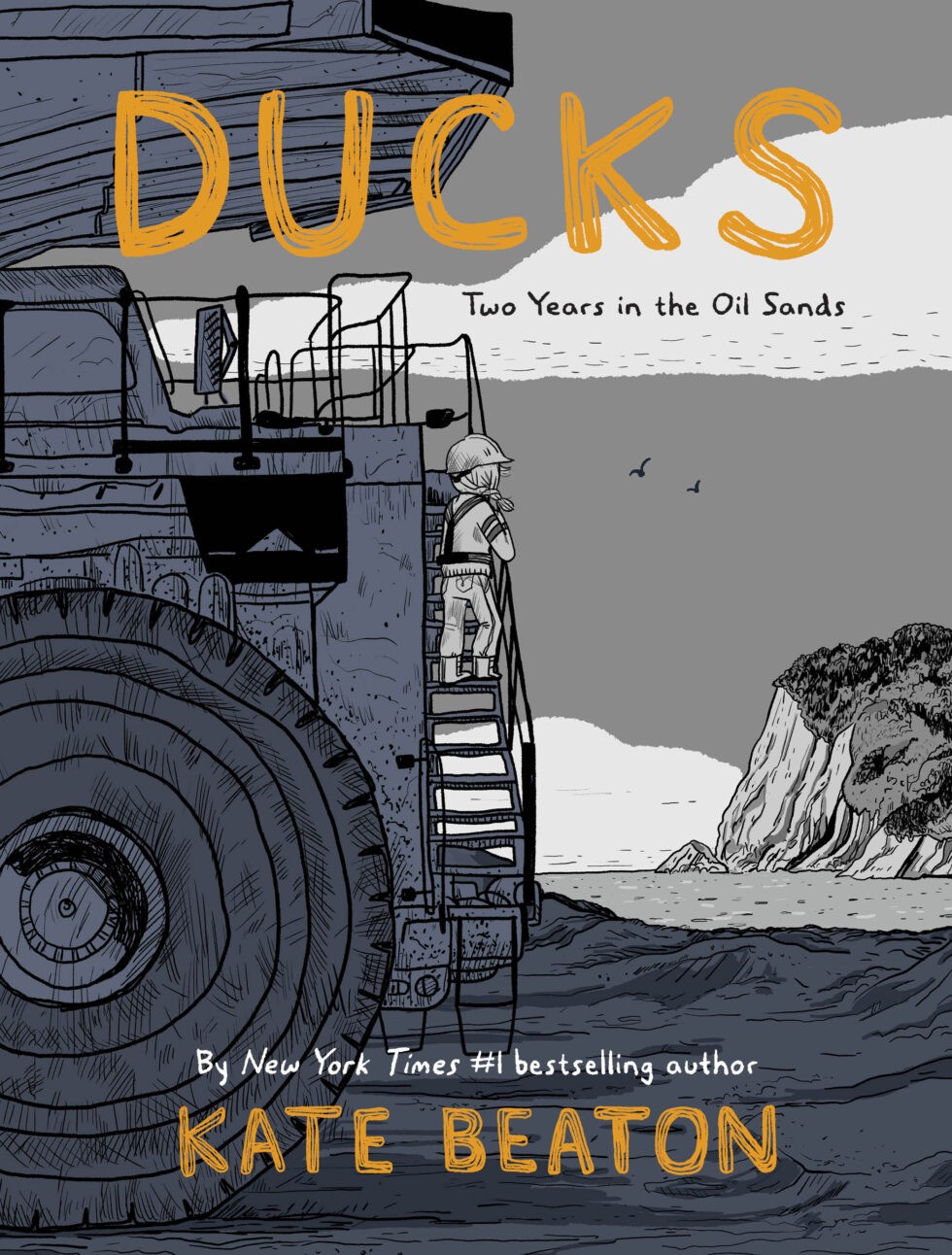

5. Ducks by Kate Beaton (November 2022)

5. Ducks by Kate Beaton (November 2022)

“The heart of Beaton’s story is the pressures that put people there – the hollowed-out Maritime economies, crude’s easy money, and capitalism’s at-any-cost ethos. She suggests that traumatized workers, wildlife, and Indigenous people are the oil industry’s collateral damage, all trapped in this devastated place like stuck ducks. Nobody seems to particularly want or like life there, and yet they stay, on and on.” – Emily Raine

6. Der Eydes Volume I & II by Cesario Lavery (March 2023)

6. Der Eydes Volume I & II by Cesario Lavery (March 2023)

“One of the great pleasures of Der Eydes is its meanderings: it’s all about the tangent, the side quest. We follow Lavery’s curious eye as he uncovers aspects of Shatan’s identity, many of which open up onto unexpected new vistas. ‘All of this unfolded by following these little threads,’ Lavery says, ‘kind of gathering them and braiding them together. In the first issue, I really talk about hunting for treasure. And whether you’re intending it or not, a sort of pattern emerges from that. So I’m thinking of this as gathering the little treasure stories.'” – Anna Leventhal

7. A Ballet of Lepers by Leonard Cohen (March 2023)

7. A Ballet of Lepers by Leonard Cohen (March 2023)

“Cohen is always at his best when he describes the beauty in the ordinary, and in his prose this is often anchored in descriptions of the Montreal of his youth. The stories in this collection, like passages in The Favourite Game, capture the Montreal of sixty years ago. The narrator of ‘The Jukebox Heart’ courts a girl by showing her, as they walk along de la Montagne, ‘a lovely iron fence which had in its calligraphy silhouettes of swallows, rabbits, and chipmunks.’ In this same piece, Cohen’s abiding focus on the seasons continues. A paragraph opens with ‘the night had been devised by a purist of Montreal autumns.'” – Liana Bellon

8. An Inner Grace by Elizabeth L. Abbott (November 2023)

8. An Inner Grace by Elizabeth L. Abbott (November 2023)

“An Inner Grace fictionalizes Maude’s life from its earliest days, making clear that she overcame every kind of childhood trauma through determined and joyful brilliance. That she grew up surrounded by the elite and powerful lent her many advantages, but she distinguished herself from even that privileged setting by establishing the dangerous and thrilling precedents that she did.” – Jocelyn Parr

9. We, the Others by Toula Drimonis (November 2022)

9. We, the Others by Toula Drimonis (November 2022)

“In the book, she presents alternative views of integration, as, in Legault’s disingenuous words, ‘une richesse.’ We, the Others’ strengths are in Drimonis’ willingness to dive into the history of xenophobia in Canada, and current controversies around immigration and language in Quebec. It is a very necessary, eloquent book, representing the allophone perspective, and an alternative view of immigrants’ contributions to a modern, cosmopolitan society.” – Elisabeth Gill

10. Alone by Paul Tom (March 2023)

10. Alone by Paul Tom (March 2023)

“Blunt, heartbreaking, and hopeful, Tom’s text in translation by Arielle Aaronson gives them [the many hundreds of child refugees who arrive in Canada] voice. Stranded in Nairobi with his brothers, waiting for a call from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees after the death of his mother, fifteen-year-old Alain despairs: ‘We don’t know when our suffering will end and the happy days will begin.'” – Meaghan Thurston

***

Interestingly enough, while the above stand-out reviews are those published within the past year that caught the eyes of many, there were also some older reviews that garnered attention. As a fun bonus, here are some of mRb‘s earlier reviews that resurfaced this year!

*

1. Tatouine by Jean-Christophe Réhel (November 2020)

1. Tatouine by Jean-Christophe Réhel (November 2020)

“Tatouine is a novel steeped in the burden, shame, and absurdity of having a body. Cystic fibrosis looms like a darkening cloud over the protagonist’s life. He’s constantly coughing up bloody phlegm, battling a series of lung infections that inevitably force him into extended hospital stays. He struggles with his weight, all the while compulsively eating fast food. At the same time, the body is very much a source of hilarity.” – Dean Garlick

2. The Murder Stone by Louise Penny (October 2008)

2. The Murder Stone by Louise Penny (October 2008)

“In The Murder Stone, Penny does a witty takeoff on the English country house party mystery, à la Gosford Park, profiting from the opportunity to take an upstairs/downstairs view of guests and staff. Even funnier is her merciless view of a highly dysfunctional WASP family, mirrored in the astonishment of the down-to-earth francophone detectives. Among these last, however, is dapper Inspector Jean-Guy Beauvoir, deeply unhappy at having to get his fine leather shoes and elegantly casual linen shirt wet and muddy…not to mention being bothered by those pesky bees, blackflies, and mosquitoes.” – Elspeth Redmond

3. Rent Boys: The World Of Male Sex Trade Workers by Michel Dorais (April 2005)

3. Rent Boys: The World Of Male Sex Trade Workers by Michel Dorais (April 2005)

“The war on prostitution closed the brothels and opened up a market in street corner soliciting, a practice Dorais recommends legalising. Sex work, he says, offers no easy exit. Male prostitutes aren’t controlled by pimps, but the transition to a conventional job or adult education is difficult. The solution, he says, is to develop a more caring and tolerant society that reaches out to marginalised individuals such as the young people who practice sex work. ‘We have, as a society, the resources necessary to help prostitutes move on in life, as long as these are made genuinely available, accessible, and welcoming,’ he insists.” – Joan Eyolfson Cadham

4. Mediocracy by Alain Deneault (September 2018)

4. Mediocracy by Alain Deneault (September 2018)

“‘Mediocracy,’ Deneault writes, ‘encourages us in every possible way to doze rather than think, to view as inevitable what is unacceptable and as necessary what is revolting.’ How terrifying that the rising from such slumber has largely not been towards creative, collective liberation but away from it, to the tyrannical violence of homophobia, misogyny, racism, and xenophobia. – Yutaka Dirks

5. The Weight of Snow by Christian Guay-Poliquin (July 2019)

5. The Weight of Snow by Christian Guay-Poliquin (July 2019)

“As you read through and begin to realize just how austere the setting and style really are, a kind of claustrophobia sets in, but Guay-Poliquin keeps it engaging – and the brevity of his chapters nicely breaks up what otherwise could have been a slog. Throughout, he offers intriguing hints that he could have painted a much broader canvas or expanded his focus considerably in any number of directions, but simply chose to do less: the mark of a clever writer.” – Malcolm Fraser

0 Comments